Tel Arad National Park

Tel Arad is a unique site in many respects. It contains ruins from two distinct period on the same hill – a large city from the Early Bronze Age and a Judean fortress from the time of the Israelite monarchy. The Early Bronze Age city is dated to between 3,000 to 2,650 BCE, after which it was abandoned. Other examples of Early Bronze Age settlement exist, but they were invariably built over during later periods, and Tel Arad is the only complete city in the world from this time. Some of the ruins have been partially reconstructed and informative signs with pictures show how the buildings would have looked.

The must-have guide for exploring in and around Jerusalem

"In and Around Jerusalem for Everyone - The Best Walks, Hikes and Outdoor Pools"

For FREE, speedy, home, courier service from Pomeranz Booksellers in Jerusalem click here (tel: 02-623 5559) and for Amazon click here. To view outstanding reviews click here.

Directions: Enter “Tel Arad” into Waze.

Admission: : This is a site of the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. Summer hours are Sunday to Thursday and Saturday 8.00 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Friday and holiday eves 8.00 a.m. to 4.00 p.m. In the winter, closing time is one hour earlier. Entrance to the park closes one hour before cited closing time. Admission is 16 NIS for adults, 7 NIS for children, 14 NIS for students and 8 NIS for seniors. Their phone number is 08-6992447. This is their website.

Public transport: Enter “Tel Arad” into Moovit. There is a bus from Tzomet Arad. There is a 1.8-km/23-min walk to the tel from the closest bus stop.

What distinguishes an “Early Bronze Age” settlement?

Prior to the Early Bronze Age, in the prehistoric period, people engaged in agriculture in small villages. Domestication of crops and animals had already taken place during the Agricultural Revolution. But there was no writing yet.

The Early Bronze Age marks the onset of urbanization. The first city-states in Mesopotamia developed in Uruk and Ur. There were early dynasties and monumental architecture in Egypt, and metallurgy and trade were found in Anatolia. Here, in Arad, we see a well laid out city with city walls, gates, organized streets, and public buildings.

This was a time when writing developed — cuneiform in Mesopotamia and hieroglyphics in Egypt. However, writing had not yet spread to the Levant. We are therefore no written records, and our knowledge of this period is based entirely on archaeology.

The Early Bronze Age was a time of specialization with fulltime craftsmen, such as potters and metalworkers. The production of bronze made from copper alloyed with arsenic or tin was introduced, and metal tools and weapons increasingly replaced stone. Social stratification was evident and there were elites together with specialists and laborers. A cultic center is seen. Long-distance trade networks were established.

As for other settlements in the Early Bronze Age, Arad was abandoned in about 2,300 BCE, and the population dispersed to small villages and seasonal pastoral camps, but not fortified cities. It is far from clear why their cities were abandoned. Suggestions include climate change with aridification, a shift to pastoral nomadism, and overextension of early urban systems. The bottom line is that we do not know. Nevertheless, this period did set the stage for urban renewal in about 2,000 BCE, in the Middle Bronze Age.

TOURING THE TEL

THE EARLY BRONZE AGE CITY

The wall of the city was made of stone and was about 1,200 meter in length and 24 meter thick. It was possible to walk on it. Towers protruded from the gate. The walls were built at one time suggesting a strong centralized authority.

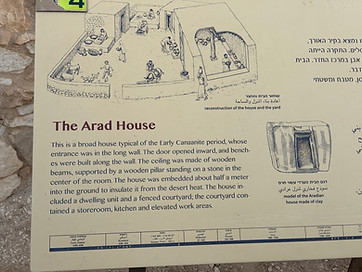

The houses had a uniform style called the “Arad House,” and a partially reconstructed example is displayed. It was a stone structure. The floor was a bit lower than street level to insulate it from the desert heat. There were stone benches along the walls. At the center of the hall was a wooden pillar that supported a flat roof of wooden beams. Adjacent to the dwelling area was a fenced courtyard containing a storeroom, kitchen and elevated work areas. A small clay model of a house was discovered in the excavation and this helped archeologists figure out what this house looked like.

The Palace. This was a large complex of many rooms, cubicles and courtyards. Its location between the western city gate and the water reservoir testified to its governmental role.

The Temples. Close to the Palace is a complex of buildings surrounded by a stone wall, constituting a pair of large temples, a pair of small temples and a single temple. Each temple had a broad room with a yard similar to the “Arad House.” Similar temples were found at En Gedi from the Chalcolithic period and at Megiddo from the Early Bronze Age. Within the temples were found stone monuments, altars for sacrifices and ceremonial basins. The facades of the temples and the ritual structures faced east towards the rising sun. The presumption is that the multiplicity of temples indicates the worship of several gods.

Water Reservoir. Rainwater drained off the slope and was collected in a reservoir. A 16 meter deep well was dug within the reservoir during the Israelite period.

THE JUDEAN FORTRESS

A well from the Israelite period inside the Early Bronze Age reservoir.

In this park is a small Judean fortress from the 8th to the 6th century BCE that measured only 50 x 50 meter and which was one of a series of fortifications protecting the southern border of the kingdom. During the monarchal period, six fortresses were built in Arad, one on top of each other. This last fortress was destroyed in 586 BCE during the Babylonian conquest. Four more settlements were built over it in the Persian, Hellenistic. Earlv Roman and Early Islamic periods.

The first fortress was fortified by a casement wall while the five that followed had a solid wall. The entrance was protected by a gate with two tall towers. It had a planned street system, residential quarters and public buildings and evidence of water management and storage.

Of considerable interest is a small Temple in the north-western corner that was in use concurrently with the Temple in Jerusalem. Its plan is the same as the Jerusalem Temple with an inner courtyard, leading to the temple, and three steps from there leading to the Holy of Holies. The Temple is to the west of the courtyard, so that as in Jerusalem, the Temple is facing towards the west, and not the east as pagan in temples.

In the middle of the courtyard is a square altar built of small stones and faced with unchiseled stones. This complies with the biblical prohibition against building an altar to God with chiseled stones made by a metal tool.

At the sides to the entrance to the Holy of Holies are two incense altars, one bigger than the other. Chemical residue analysis on the altars detected frankincense and cannabis resin mixed with animal dung (the latter likely to aid combustion). The cannabis may have induced altered states of consciousness and enhanced ritual experience, suggesting sensory dimensions of worship not described in biblical texts.

Within the Holy of Holies are two monuments or matzevot, again one bigger than the other. It is not obvious in the first picture below that there are two monuments, since the smaller one is behind the larger one. The picture below shows that they were not formerly so and someone must have moved them. The issues are why there are matzevot at all, and particularly why there are two? Even one is biblically forbidden, and certainly two!

One suggestion is that the One God was thought to have a female partner. Elsewhere in the Sinai Peninsula on storage jars and plaster walls have been found the sentences “I bless you by Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah” and “I bless you by Yahweh of Teman and his Asherah.” In Khirbet el-Qom, in the Judahite Shephelah, and on a late 8th century tomb was found the inscription “Blessed be Uriyahu by Yahweh, and from his Asherah he has been saved.” The phrase “Yahweh and his Asherah,” suggest that some Israelites and Judahites understood Yahweh’s worship as involving an associated Asherah—whether she be a goddess, symbol, or cultic object. These texts provide the closest textual parallel for interpreting the paired standing stones in the Arad temple. Alternatively, the second smaller standing stone or matzevah represents a symbol of Yahweh’s presence, and not a second deity.

This Temple went out of use in the late 8th century BCE and the entire site was covered over. This may well have been due to the religious reforms of King Hezekiah, who attempted to make the Temple in Jerusalem the sole place of worship for the Judeans. He may also have been concerned that the worship of God in out-of-the-way places was no longer pure monotheism.

Within the boundaries of the Temple were found ostraca with names of priestly families mentioned in the Bible (Ezra and Jeremiah).

In thios picture the second matevah is hidden behind the larger one.

In this picture, the two incest altars and matzevot can be clearly seen.

Elyashiv House: There is nothing unusual about this house close to the southern wall of the fortress other than it contained an archive of ostraca written mainly in ancient Hebrew. Seventeen were addressed to Elyashiv, apparently the commander of the fortress.

The Water Facility. This is located close to the Temple and consists of three excavated and plastered cavities. The original staircase leading to them has only partially survived.